Click here for photo gallery of the Tahiti & Marquesas Islands trip!!!!

Tahiti and The Marquesas Islands

My, my how domestic air travel has changed. I remember in the 1970s when I represented The Organization to Manage Alaska’s Resources and would fly first class from Washington Dulles to Anchorage, through Chicago. On the Northwest 747 the first class cabin contained a lounge, up the spiral staircase to the bubble behind the flight deck. Today, all airlines use seats in that space for more revenue. The chairs swiveled around, and after a great meal served with real Champaign from Reims, I would climb to the lounge, look out at the world far below with my feet in the window frame and ponder great thoughts. The flight crews in those days were served first class meals by the stewardess’. Yesterday, before our American Airlines flight boarded at Dulles I watched our flight captain enter the gangway holding a Subway sandwich encased in a plastic bag. The only constant is change.

I could not care a whit if I have to buy my lunch on the new, deregulated, highly competitive U.S. commercial air system. Our coast-to-coast five hour American Airlines tickets cost us $342.80 each round trip total; unbelievable! Further, our flight attendant (as opposed to the above stewardess) was upbeat, cheerful, attractive and accommodating. Lisa Johnson’s service was a throwback to the days when airlines would charge anything they could con the government into allowing and air travel was a positive experience, if noncompetitive and expensive. American Airlines should give Lisa a raise and hold her up as an example to her often grouchy colleagues.

It seems that each ship we step foot upon over the last few years misfires or in some way needs repairs. The last two voyages we undertook on the Maasdam resulted in broken engines. Of course, the Repubblica di Genova has capsized. Today, we are not underway because the Aranui has a busted engine pump that is being replaced, but that has been the least of my worries of late.

I have been re-attacked by a vile and vicious Jewell Hollow blood-sucking tick. Our daughter-in-law pulled the miniscule killer from a small spot beside my right arm pit on Jeanne’s birthday, March 31. It was for us in the Shenandoah National Park a normal tick, not the much smaller, black Lyme Disease-causing leecher. Ten days later the spot the little beast attacked had inflamed into a hot spot the size of a salad plate. To Valley Internal Medicine I marched, followed by 10 days of antibiotic therapy. Problem solved; well, not quite.

The evening of our short sojourn in Los Angeles we were hosted at Dinner by my law school seatmate friend of closing-in-on-50-years Rick and his companion Alexis. Rick and I had a couple of martinis each, some wine with the meal, which resulted in a long lecture from Rick on the absolute necessity for U.S. gun control and confiscation. He spent his career lawyering in Northern Europe and is convinced that the no-guns European model could somehow become viable in the U.S., despite an estimated 200,000,000 guns afloat in the land and millions people willing to cause considerable mayhem in order to keep them. No conversions to his religion were made, but the long friendship endures.

The eight and a half hour flight to Papeete was uneventful except for two observations: The Air Tahiti Nui cabin crew was meticulous in its devotion to cleanliness, stooping to pick the slightest piece of trash from the carpet as they passed through the back of the Airbus and darting in and out of the lavatories to check the conditions therein and make any needed improvements. Thanks to gate manager Diane Gomez in Los Angeles, Jeanne and I were given exit door row seats with unlimited leg room, with no seats in front of us (and a near and clear view of a bank of lavatories.) A tip of the Frink fedora to Ms. Gomez.

During the flight I became chilled and by feeling my forehead with the back of her hand Jeanne came to a near-certain conclusion that my fever had returned; she was correct. The damned Jewell Hollow toxic tick had regrouped and was ferociously counterattacking my body after the original antibiotic therapy had run its 10 day course. The physician the Sofitel Tahiti Resort staff called to my aid bills himself as SOS Medicine. While he didn’t save out ship, he certainly saved our voyage through the Marquesas Islands on the Aranui-3. Trained in France, the doctor knew upon inspection of my newly re-reddened and re-heated underarm that the tick had returned to haunt me; he called it a secondary infection.

He had antibiotics in his large over the shoulder travel bag and began my new therapy on the spot; he ordered at least 900mm of aspirin a day to fight the fever, now four degrees above my normal. In the morning Jeanne returned from the Pharmacia with enough medicine to be taken three times a day for seven days.

Before Dr. SOS and because of the high fever, we discussed canceling out the voyage and making the 13 hours of return flights home immediately; Saturday, after his treatment, we gave up our room and balcony facing the serene scene of swimming pool and curved lagoon and forged forward. We were driven to the pier through traffic-jammed Papeete. Up the gangway we went, to another cargo ship and another adventure. I slept most of the first day and all night on the ship and awoke Sunday morning a renewed human being.

When aboard cargo ships, as I have previously expounded on this website, you don’t know where you are going and you don’t know when you will get there. The Aranui is hurrying to Ua Huka, the furthest of the Marquesas Islands from Tahiti. We have aboard a replacement generator for the island; theirs imploded and the island is totally without electricity. We are steaming to the rescue, though in fact the islanders have already suffered the loss of their perishable foodstuffs and medicines.

It is Tuesday and the Aranui is embarked on a 2,200 mile round trip to the Marquesas Islands. Of the 20 islands or islets that make up the island group, only six are inhabited. Our ship is the lifeline to each, carrying everything from bandages to backhoes.

The Aranui, with its almost 100 passengers, is navigating through one of the most remote areas of the globe: We are, or soon will be, approximately 3,000 miles from Hawaii, 2,600 miles from Easter Island, 2,800 miles from Galapagos, over 900 from Tahiti and 4,500 miles from Los Angeles. We are on our way to a few miniscule volcanic specs in the overwhelming vast Pacific Ocean. On the six inhabited islands scattered within the Marquesas group there are only 9,104 folks total living in the splendid isolation, referred to throughout the ages by the likes of R.L. Stevenson, Herman Melville, Robert Michener and even the contemporary American novelist Larry McCurtry, as paradise. We shall see.

Our ship fits its task perfectly: first, carry the necessary items of 21st Century life to people on remote drops of hardened lava in the Marquesas Archipelago; second, carry along in reasonable comfort some folks adventuresome enough to plunge by sea deeply into the Polynesian Triangle (Hawaii, New Zealand and Easter Island), where few have ventured before.

When I was in the midst of my 47 day voyage aboard the Repubblica di Genova I was excited to receive an email from Bruce, who was so excited by my depictions of my life aboard the ship that he read 20,000 or more of my expertly crafted words in one sitting. A great man, Bruce. He would like to enjoy at least one cargo—or freighter, if you wish—voyage in his life. Alas, Bruce’s wife enjoys the pampered creature comforts of a cruise ship. Bruce, Pal: Don’t book her aboard the Aranui-3—not her cup of tea. A cargo ship, no matter how comfortable it is for its many, or limited number of, passengers is not a cruise vessel. The Aranui does not have multiple dining sites or choices at meal times. It doesn’t have a spa, casino, or grand atrium. It doesn’t change the sheets and towels every day, let alone twice, needed or not. There is no cabin steward to bring you ice, and otherwise suck up to yourself important self. It is a close call, Bruce, but I don’t think Mom would make it through Polynesia a happy camper. Of course, it’s your call, Bruce. You know her better than I.

Grant’s company develops real estate in Auckland. It owns over 300 detached houses, which are rented out. Their son heads the real estate management end of the business. Here’s a guy who has a leg up to win the World Cup for entrepreneurial Pizzazz: One of Grant’s partners in another enterprise is a Singapore Chinese dude who owns 35 million acres of land in the Philippines. He is presently planting it with a vegetable oil producing, fast growing bush. The Chinese fellow is pouring in a few tens of millions of dollars to create his own deep water port. Once completed, the plan is to squeeze the oil from the bushes and export it to the U.S., to be used as biodiesel fuel. Christine is in the tourist business in Auckland, and her non-Grant son is easing into control of it. Christine and Grant are a low key, charming couple and Jeanne and I enjoy their company.

The skies unloaded a warm, intense rain. I didn’t melt; ergo, an important lesson was learned. It was 7:15 am and we had breakfasted and walked off the Aranui at dock and were ambling along the beach “road” past tethered horses and free-range roosters into the village of Taiohae, population 1,944, more folks that any other town in the island chain. Our path took us past the grand, pink colonial home of the French administrator for this, the northern, portion of the Marquesas. We were beginning our day-long exploration of Nuku Hiva, the largest island in the Marquesas archipelago. We were early-morning strolling in the rain in quest of a facility that would allow us to email four dispatches from far-out paradise. It was found in a yellow frame gift shop—internet outlet—in the marina, with the help of a thin Frenchman riding a mountain bike. Close by in the bay, visiting sail boats and one large motor yacht lay lazily at anchor.

All Marquesas Islands resulted from volcanic eruptions out of the sea. As the exploding lava reached its highest point and began cooling, it created peaks and pillars at the top of the lava pile forming a particular island. The Aranui crew’s excursion plan for the day was to drive the passengers from the port of Taiohae up over the lava mountain peak and down to Hatiheu, a valley town on the other side. I don’t know what was going on with the French within the air conditioned SUVs, but from the back of our truck laughter often burst out as we hit pot holes, one after another, in the rocky—not ready for highway designation—mountain path/road. “We had great fun in the truck. It was open, we could see all around us and the air was fresh. We all laughed at the bumps,” Jeanne said later.

The Aranui retreated from Atuona Bay barely under power. Bob Suggs explained that the captain has to “feel his way” because of the very shallow bottom. Suggs and I moved from starboard to port on the main deck and saw a second reason our exit from the Bay was uncommonly slow: In the dusk, one of the ship barges with four men aboard was being plucked from the sea by the crane operator above. We were unloading at dock all day, so the mission of the barge is a mystery.

Today was Calvary Cemetery day for the Frinks on Hiva Oa, yet another tropical island in the remote Marquesas. The French painter Paul Gauguin is legendary in French Polynesia. He came to these islands in search of the “savages” as my physician in Tahiti referred to the Marquesans. Suggs assures me that the Tahitians consider the inhabitants of the Marquesas to be inferior and that it is deeply resented by them. Gauguin found inspiration for his work and the love of a number of Polynesian women who, in turn, produced little Euromarquesans. Gauguin is a French Polynesian brand: his images and words are exploited endlessly (Gauguin’s words were even woven into the sheer curtains of our hotel room in Papeete.)

When Gauguin arrived in Atuona he was befriended by Ben Varney, an American merchant who vended his wares from the Yellow Store; it is located across the road from the land that Gauguin was finally able to con the Catholic Bishop into selling him, now the site of the museum. The Yellow Store lives. The Yellow Store is real; real, open for business selling cold, 16 oz. bottles of Tahitian beer. After the imitation Gauguin museum, the Yellow Store brought us pleasantly back to reality.

Today, perhaps, we reached Paradise. Fatu Hiva is only nine miles long and three and a half miles wide. Less than 600 men, women and children populate this lush, foliage and palm-tree covered dot in the Marquesas chain. Its tallest peak is 3150 feet. The only strangers to ever reach this verdant lava chunk jutting out of the South Pacific, with its vast, sheer-walled valleys reaching up to the peaks, are a very few visitors from foreign sailboats anchored in the bay and the passengers the Aranui disgorges for two hours or so every three weeks. “There is no place like this in the Caribbean,” Jeanne pronounced as we were about to climb the mother ship metal gangway, after visiting our second Fatu Hiva village this day.

The green launch bobbed up against the slippery concrete dock. Passengers were individually discharged on the up-swell, firmly grabbed by strong Aranui seamen and passed seaman to seaman until safely on the dry concrete. It was then a short uphill walk and a stroll down and behind the long, mildly agitated beach. The homes along our path were tidy; one fenced in by metal posts set in concrete connected by wire fencing, the yard virtually covered with pots of flowering plants. In this tiny village, was the owner keeping out animals or persons?

“Eight children, five boys and three girls, and now they are all gone, to learn and to work.” He amended that statement later, explaining that his 16 year old son was still at home. Most of his children are in Tahiti. “I have been camping for three weeks. I have friends here.” He lives in Vaitahu and was about to break camp and walk home over the mountain. “I like to walk.”

“We don’t need much to live,” he said in replying to my question about the lack of jobs on the island. “When I first came to this island, there were no stores, no electricity. We fished everyday and ate fish and breadfruit.” To my inquiry as to his ownership of a boat, he replied: “I had a boat, but no more. The gasoline is too expensive.” When he must operate on the monetary economy, he makes copra (smashing coconuts, removing the meat and air-drying it.) In a follow-up conversation in French, Dr. Fine, our ship doctor for this voyage, learned that Jean makes $10 for a burlap bag full of copra. Obviously a man who enjoys parenthood, during our conversation he offered: “I would like to find a younger woman so I can have a family of children again.” Dr. Fine told me that Jean said that he liked to move around a lot. We agreed that meant Jean and crew probably had never possessed a permanent residence. Dr. Fine opined the Jean might be unstable; given Jean’s primitive life style in far-off Paradise, I disagreed. The sum of this Tahiti born Frenchman, who probably has never had a wage job in his 54 years, was his statement to me early in our conversation: “I am a happy man.”

Most passengers were hauled up to the two-tiered 200 by 275 foot ceremonial site in pickup trucks; some took a mountain walk (Steffi, a German woman, assisted by two metal telescoping walking sticks that look exactly like ski poles). “Planning on skiing, were you,” I asked. It was a weak attempt at humor.

Bob Suggs gave a lecture in English that was translated into French by one of the staff. The Germans and Austrians got a paraphrased version, given by another staff member. It is believed that the Naiki Tribe (think athletic shoes for pronunciation) began to build the site in the 15th or 16th century. Again, it is believed that three chiefs of the Naiki Tribe living in the tiki neighborhood captured, cooked and chowed-down upon the chief of a neighboring tribe. The consumed chief’s brothers came after the Naiki boys, killed many and ran the rest off. It was the survivors of the cannibalized chief, Tiuoo, who, in his honor, began construction of the site. Now, on to the tikis.

Bob Suggs’ life has been interwoven with the Marquesas Islands. While working for the American Museum of Natural History in 1956 he was sent to the little-know island chain to begin the first archeological excavations in French Polynesia. He has returned to the archipelago regularly in the intervening 50 plus years. His degrees through the PhD were earned at Columbia University, which he attended after the Korean War, in which he served as an enlisted Marine. His has been a professional life of service. Now 75 years of age, he retired from the Navy as a Captain.

It was luck of the draw that Bob Suggs would be the lecturer on our Aranui voyage. He only does three voyages a year on the Aranui. His knowledge of the Marquesas is encyclopedic, aided by his fluency in Marquesan and French. He is a short, wiry man, sometimes seemingly coiled for action. His humor is wry and wit quick. He has been a very welcome traveling companion for Jeanne and me.

The sea was relatively rough today. The passengers were conveyed to Puama’u on the green launches instead of the whaleboat. Again, wet concrete and stones to contend with as the launch bobbed up and down with great authority. We were grabbed by seamen on the up-bob and pushed out of the launch into seamen’s hands ashore. On the return, Trevor, one of our New Zealand friends no longer a young man, slipped on the concrete steps and took a flop; it caused a considerable gasp among us, but the Aranui seamen grabbed him and firmly placed him where is bottom belonged, on a launch bow bench.

“It is too bad that you don’t speak the language; you miss a lot. The people of the Marquesas are so gentle, so trusting. Two nurses at the hospital even asked me how they should vote for president.” French Doctor Xavier Fine and I were chatting as we waited for a launch to take us back to the Aranui. He is at 57, a tall, thin, bespectacled man with a calm, at-ease-with-himself manner. Perhaps he is the one who has found Paradise in French Polynesia.

Dr. Fine’s medical specialty is orthopedic surgery, but in the small French Public Health Service hospital where he works all of his medical skills are needed. “I live on the hillside, overlooking the bay in Taiohae on Nuka Hiva. It is very nice.” He lives in far-out Paradise, but as a practicing physician he is a productive man. He is a French public servant, still technically under the jurisdiction of the French Health Service on Reunion Island in the Indian Ocean, where he once lived and worked. Xavier’s Polynesian wife, Beatrice, is as calm and quiet as he. She speaks English, learned in Sydney Australia, as well as French and Polynesian. She is an importer. They appear to an outsider to be very suited to each other. So there you have it: Dr. Xavier Fine, living far from the artifice of the modernized world, in the perfect climate where he sees the sea each day, working in his profession, which is much needed by the Marquesians, whom he respects, married to a Polynesian woman, he loves. To me, it all seems to fit perfectly.

The theme during the day was rain. We visited three villages on the island of Us Huka. Through welcoming dances, a short speech by the mayor of Vaipaee, Bob Sugg’s explanation of the artifacts collected in the town’s tiny archeological museum and a tour of the (now muddy) botanical garden, it rained. With Peter and Heidi, Don and Nancy, Jeanne and I were again touring an island in a pickup truck, buying more wooden “stuff” as we stopped at the craft center in each village. “We probably won’t ever get this way again,” was Jeanne’s mantra as the money flowed. After our observation of the huge stone tikis at the site of Sugg’s first Marquesan archeological dig, Jeanne and I have become tiki-addicted. There is not a wooden tiki, large or small in the populated Marquesas isles, that has not caught our eye; yesterday, there was a beautifully carved three foot guy, with mother of pearl eyes, that was too large to pack and, at $1500, too large for our remaining cash. No credit cards accepted on the more remote islands of the Marquesas, period.

Chez Celine Fournier in Hane was the best off-ship luncheon of the voyage. The raw tuna was firm and very fresh. The goat meat was tender and its curry sauce the tastiest yet. The plantains (cooking bananas) were cooked in the restaurant’s Marquesan earth oven and came out firm and with a delicious smoky-banana taste.

Each day our Aranui voyage has provided extraordinary adventures. Yesterday, it was our method of boarding the waiting launch in the surf of the wide beach, down the winding road from Hane. We passengers waded up to our knees in the active surf, out to the waiting green, wooden launch. We taller folks then stood with our backs to the launch and bounced our bottoms onto the stern.

Yesterday, we re-visited for a short time two villages on different islands: Tahiohae on Nuku Hiva and Hakahau on Ua Pou. Jeanne and I repeated our walk along the beach into Tahiohae in a vain attempt to get my daily essays e-mailed to Tom Sand, my editor in Minnesota. Outside the marina shop, wherein the internet access is located, we met Dave and Peter. They had just arrived after an 18 day sailboat voyage from Santa Barbara. “We had a pretty good run,” Peter replied to our surprise at such a short time to cover such a vast distance on the big pond with a small sailboat. “We hope to be in New Zealand by November,” he concluded.

.jpg)

We walked again in Hakahau, along the beach and up on the concrete streets, the principal settlement on Ua Pou, a ten mile long volcanic island with a 4,042 foot peak in the middle; the first westerner to see it was Boston trader Joseph Ingraham, in 1791. We bought a beer and some Coke and tonic water at a familiar shop, but did not have the time to re-visit the magnificent church, Eglise Saint-Etienne, with its huge eight foot high wood pulpit, a carved ship bow at the top sitting over an intricately carved fish net containing observable fish and reptiles. This, the most stunning wood carving we have seen among many in our march through the Marquesas, is the product of one wood carving family, the Teikitohes.

On our return walk to the Aranui, being unloaded at dock, we chatted with more American South Pacific sailboat adventurers. One Seattle couple and a friend had just completed a 27 day sail from the west coast of Mexico. “It’s not too bad if you don’t mind being bashed in the head while you’re on the john or slammed around while you’re trying to cook,” the woman said of conditions during the crossing in their 42 foot long watercraft. When I inquired about their jobs ashore, the husband, a retired computer consultant, said: “We’re not going to work again if we can get along on $2,000 a month.” Listening to them recite the $6,000 they recently paid for engine repairs and their $10,000 fresh water-making device, the jury would appear to be out on that question.

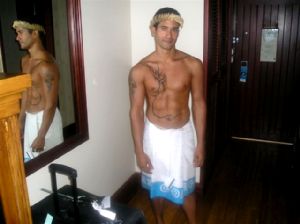

Our journey through the Marquesas is over. Presently, we are on at sea heading for Rangiroa, in the Tuamoto island chain, the last stop before our return to Papeete, Tahiti. Before our experience in the Marquesas fades from consciousness, a couple of comments. First, we were struck by the prosperity evidenced on all but islands with the tiniest of populations. Everywhere else, there were new expensive 4X4 pickup trucks and SUVs. I suspect much of gross domestic product of the Marquesas results from subsidies from the government of France. What else, copra, the few tourists the Aranui brings by every three weeks, visiting sailboat occupants? Unlikely. The second comment is about tattoos.

Volumes have been written about Marquesan tattoos; suffice it to say that when the first western ship set anchor in the Marquesas it was met by warrior men tattooed head to foot. The more a man’s body was tattooed, the greater his wealth and power. Various tattoo motifs had meaning. In the case of warriors (and the history of the Marquesans is rife with battle) large eyes were tattooed on their thighs to allow them to “see” more and therefore better protect them from their enemies in battle. For over a hundred years tattoos were banned by the Catholic missionaries; the ban existed from 1867 to 1985, when the bishop lifted it, declaring “Marquesans need something to identify themselves.” Today, many Marquesan men and women bear tattoos of various motifs. Photos on our website accompanying the essays of our South Pacific sojourn will amply illustrate examples of modern tattoos used throughout the Marquesas Islands.

From the beginning there has been a modicum of tension between the French and English speakers aboard. Some tension developed because of the passive-aggressive nature of more than one French couple, shoehorning themselves ahead in lines, slipping into sightlines of others already established to watch a dance or other tourist event. Early on, they were clannish in the extreme. One example, at meals one of them would rush into the dining room to claim the largest table and lean chairs against it, impliedly proclaiming: KEEP OUT.

Nancy, a retired California postmaster and wife of Don, retired Los Angeles County forest firefighter in the process of moving their home to Maine (HELLO-culture shock) talked about a revolutionary takeover of the French table. Plans for the revolution were made; but the evening came and no shots were fired. Nancy explained that during the day one of the French had performed a kind act for a member of the English Speaking Union, as I have labeled our collection of Brits, New Zealanders, one gritty Australian woman, a man and wife Polish pair and a passel of Americans.

The next evening without notice, Hubert, the Polish investment banker struck. He rushed into the dining room and claimed the chair at the head of “French” table. The English Speaking Union quickly filled in behind him. The French were dumbstruck; as would be expected, many pouted. We were gleeful throughout the meal and wondered aloud if the French would present us with terms of surrender, in order to get their table back. A point having been made, during the following meals the ESU withdrew to its member’s customary tables.

The moment of truth arrived. The French went on first. They sang a song or two without passion, no choreography, no zip to their performance. The English Speaking Union followed. I announced the act. Then we hit it, with verve and vigor: Sail Smooth, Sweet Aranui.

The dolphins came to play. The passengers were alerted to the possibility that the amazing seagoing mammals would “attack” the ship as we were about to enter the lagoon off the atoll of Rangiroa, at 47 miles long and 16 miles wide the second largest in the world. Jeanne caught four dolphins in one photo, as they swam with the ship on the starboard side. As they played with us, some of the dolphins—correctly small toothed-whales—would break the water surface as their backs arched. Soon they were gone. I will not soon forget Damiano, a third mate aboard the Repubblica di Genova, proclaiming his admiration of the dolphins, which had come to play that day, with that ship: “They are so wonderful because they are free.”

We enjoyed lunch on the lagoon beach today, part of a multifaceted excursion under the direction of Aranui cruise director Bernard Naas. Of Alsace origin, he is a shaved-head, burly bundle of energy, who speaks all three languages featured aboard ship: French, English and German. He has given off positive vibrations, wherever we have encountered him aboard ship or ashore. The 47 year old father of a 19 year old daughter and 12 year old son, he and his wife and family now make their home in Papeete. A retired 21 year veteran of the French Navy, which stationed him in French Polynesia for two years ending in 2001, he returned to Tahiti at the urging of his children. He hooked up with the Aranui through an ad in a Tahitian newspaper and has been with the ship for two and a half years. This year the Aranui will make 16 voyages through the Marquesas, next year 17. Bernard works each two week voyage and takes a week off ashore between them.

An atoll is a flat coral reef, so different from the volcanic mountain islands we have been experiencing throughout the Marquesas. The shallow water beaches are wide and the bottom clearly seen through the clear, clean azure water. A small group of us walked a few yards down the beach to the Kia Ora Resort. It appeared to me to be exactly as Hollywood would create a Polynesian resort: Thatched roofed bamboo bungalows facing the lovely Rangiroa Lagoon, some on stilts sitting over it. I obtained a resort brochure from a woman employee speaking Japanese with a young couple; the backpack on the young man announced in English that it was made in Japan. Three Italian couples waiting to check in sipped fruit punch nearby. The brochure revealed that at the Kia Ora Resort an over-the-lagoon bungalow will exact 570 Euros a night from your net worth, or approximately $700. Food, of course, is extra. “And that doesn’t include the air fare,” Jeanne said. I replied: “This place is for people who have all the money in the world.” She ended the topic: “If I had all the money in the world I would be on a ship going around the world.” We hightailed it back to the whaleboat, a short spin on the blue lagoon, up the ship-side metal steps and we were back on the Aranui.

Tomorrow this marvelous, nearly flawless (on the beach today I heard one of the bar flies complain that it wasn’t organized enough ashore) adventure ends. These two weeks aboard the Aranui have been a traveler’s dream come true: being introduced to a far away Polynesian culture few westerners have ever encountered, while living in comfort aboard ship with a variety of civilized, interesting people, passengers and crew alike. It is difficult to pack up and face the fact that it is over.

The tropical weather and sea breezes mean you never have to heat or air condition your dwelling in Paradise. The piercing sun shines relentlessly. Polynesians predominately are kind and giving. We are going to miss The South Seas.

As the passengers were gathered in the bow of the Aranui yesterday anticipating the dolphins show, Dr. Fine told me a story illustrating the gracious nature of the Polynesians. “Thirty five years ago, in the last year of my medical studies, I was on holiday on the atoll ahead, Rangiroa. I had a spear gun, four feet long, and was on my way to dive. I passed a man who signaled to me that my gun was too short. He went to his house and came back with a gun two meters (six feet) long and insisted I use it. When I returned it he asked where my luggage was. I told him that is was in the hotel. He told me to bring it to his house, that I must stay with his family. I stayed a month.”

The food aboard the Aranui was spectacular. Our last dinner was a first course of genuine, warm foie gras, followed by rack of lamb and a baked concoction with raspberry sauce for desert. One evening, a somewhat strange German woman special ordered pizza, if you can imagine. The serving staff was cheerful and efficient. The wine supply during the midday and evening meals was inexhaustible (and we had some heavy hitters on the wine bottles at our table.)

Our dining companions were story tellers, or at least the men. Peter is a former British Bobby, as is his wife, Heidi. They have been on a three month sojourn that has taken them to South Africa, Australia and, of course, to French Polynesia. Peter seemed to have a new Bobbying-run-amuck story each evening. Unfortunately, he and Heidi were stung by jelly fish while snorkeling in the Rangiroa Lagoon and Heidi had an uncomfortable medical reaction.

Don, our retired Los Angeles County forest firefighter, told stories about the convicts he wrangled as members of his firefighting crews. His wife, Nancy the retired Postal Service postmaster supervisor, told us of the crooks on the outside and within post offices and how they prey on mail recipients. With Grant and Christine, their stories of their lives in New Zealand were fascinating. Rick, a law-degreed investment advisor, chimed in intelligent comments on whatever was going around the table. Bob Suggs was the anchor of our dining table. There were always new stories of his decades of involvement in the Marquesas Islands. It will be lonely for a time in Jewell Hollow, as Jeanne and I sit down for our evening meals.

Our adventures continue: We are marooned in the vast Los Angeles international airport (LAX.)

The return leg of our fascinating journey into far Polynesia began with a caution. Mai, of South Pacific Tours, was 20 minutes late picking us up at the Tahiti Intercontinental for the short trip to the airport; that meant we had no possible claim on the most desirable seats on the Air Tahiti Nui flight, which was, unlike our LAX to Papeete leg, chock full. It was as good an eight hour flight as the back of the bus allows: genuinely gentle and attentive flight attendents, adequate back-of-the-bus food and as much Champagne as I wished to imbibe. The trouble began after landing in Los Angeles.

The American Airlines 737, bound for Washington Dulles, was loaded, carry on gear stowed in the overheads, the passengers buckled in. Then came the deep baritone voice from the flight deck. “Well, folks, I want to apologize for our late start today. The equipment was a little late getting to Los Angeles. At the moment, technicians are doing a little maintenance on the aircraft. A couple of flight crews have noted a problem with the reverse thrusters; they enable us to slow down more quickly upon landing. Of course, we really don’t need them at Dulles because the runway is so long. Stay in your seats and I’ll get back to you in a moment with an update.” In a few moments, before the captain opened his mike again, I heard from passengers across the aisle from us: “They’re taking our luggage off the plane.” The captain’s exit speech began with: “Well, folks…”

American Airlines staff did a remarkable job assisting their stranded clients: Extra personnel quickly appeared at the gate podium, instructions given were clear: “for those of you at the back of the line, those of you with cell phones might wish to call reservations directly; the number is 800…” Jeanne reached Richard Raut, DRR, in Raleigh NC. He initially put us on an American flight leaving tomorrow at 2:15 pm, through Dallas-Fort Worth, arriving in Dulles after midnight Tuesday morning (it is Sunday evening in Los Angeles as I write this.) Jeanne pled with Mr. Raut that she had serious business in the Page County Sheriff’s Office Monday. After a 15 minute pause, the able Richard Raut came back and said he could put us on a United flight to Chicago that hopefully will put us on the ground at Dulles just prior to 9 am Monday. We got a baggage transfer from Kirk, an affable blond fellow on the American counter, claimed our luggage as it bounced out of a carousel a flight down; we wheeled it four terminals away, signed on with United, rechecked the bags and again passed through security, shoes in one plastic bin, the computer in another. We await our 11:15 flight to Chicago.

Yesterday I spotted a long snake swimming the length of the pond. I knew it would disappear into one of the cracks below the rock wall that half-moons the west end of our petite body of water before I could scramble into the cabin, load the shotgun and return. Regardless, I procured the shotgun from its cabin corner, loaded it, walked around the pond a bit in vain hope, then placed it, loaded but with the safety on, on one of the tables in the summer house. When I next spot a swimming snake I will be better prepared. From the Aranui and a classy Tahitian resort, to a snake swimming in the pond: We are home.

Upon reflection, little changes. Jeanne and I are travelers. We have passed through and witnessed much of the world contained in the Americas, Europe and Asia. To have the privilege to venture into the little-visited Marquesas Islands—the archipelago farthest removed from any continent—in far off French Polynesia with the comforts of voyaging aboard the Aranui was an extraordinary, if not unique, experience. As Jeanne often reminded me: “We probably won’t pass this way again.”

We have people to thank. First and foremost, our lavish gratitude goes out to Leila Laille, of the Tahiti Tourisme North American office in Southern California. She worked tirelessly with us, over many weeks and through a seemingly endless string of emails, to bring our wonderful sojourn in French Polynesia to fruition. Any reader contemplating a trip to Tahiti and the other islands of French Polynesia, I suggest you begin with the Tahiti Tourisme North American office. Our thanks to Air Tahiti Nui for the courteous staff, both ground and in-flight, who assisted us and for their high standards of in-flight cleanliness. We thank Jules Wong, Tahiti, marketing director of the company which owns the Aranui-3. We thank Tino, the 25 year veteran Aranui cargo master, who was in charge of not only the loading and offloading of the cargo, but the passengers when they were disembarking and returning to the ship and while we were ashore. Tino gave an emotional lecture aboard near the end of our voyage. I was writing and not able to attend, but Jeanne was in rapt attendance. Tino spoke of his deep pride in being part of the seaborne lifeline to his, the Marquesan people. On our voyage, Tino’s infant son was aboard, and we observed him more than once playing with the boy or proudly holding him. Our thanks also go to Captain “Ted” for a smooth voyage and a safe return. Our special thank-you to Dr. Bob Suggs for his friendship and knowledge of the Marquesas imparted during our journey.

For those wishing to further explore the Marquesas Islands and a voyage aboard the Aranui, I suggest “Manuiota’a Journal of a Voyage to the Marquesas Islands,” by the often-aforementioned Bob Suggs and Burgl Lichtenstein. It contains some of Bob’s lecture material as well as an interesting recount of an Aranui voyage.

Successful novelist and screenwriter Larry McMurtry has written a book that has something to do with an Aranui voyage into the Marquesas. It is a strange book. He set out to write about his parent’s incompatibility in the bleakness of Archer County Texas; in it we learned that his mother was a “soiled dove” (a hidden previous marriage) and the crude birth control method she used when condoms (probably called “rubbers” in those days) were too expensive during the Great Depression. The material on the Marquesas is in great part boilerplate that McMurtry picked up aboard ship, reading in the ship library. According to a crew member I queried, McMurtry spent his voyage in his cabin or as my witness said: “reading every book on Polynesia in the library”, or when other passengers were ashore and incapable of bothering him, in a deck chair. He rarely ventured ashore, convinced in his intellectual haughtiness that anything worth experiencing in the Marquesas could be observed from his favorite Aranui deck chair. The passengers aboard during his voyage were oink-oink, piggish craft shoppers or wanton Europeans virtually forcing him to guzzle unwanted wine. Don’t waste your time or money.