Click here for photo gallery of the Grande Ellade voyage!

Voyage aboard the Grande Ellade

Now that the trash has been removed and the carpenter and painter have gone on to other jobs, Jeanne and I can prepare for our flights to Naples and two week voyage aboard the Grimaldi cargo ship, Grande Ellade.

Over the 40 years plus that I have owned our Jewell Hollow cabin; I have felled tens upon tens of trees, from straight and slim knotty-barked Sycamores to huge, towering granddaddy Oaks. Oh sure, there have been occasional problems, trees that got hung up in the limbs and branches of their neighbors and had to be either wedged off the stump or sawed down in lengths; but usually it was a relatively simple matter of divining the direction the tree wanted to fall and sawing a large notch to assist it, and then sawing from behind the notch until the hardwood slowly floated to the ground, landing with an often-frightening, dramatic thump.

My last Oak tree was different. It was a tree of serious substance, tall, dead and near the end of the cabin. I had pled with Sammy Fox, my tree man, to come up and take it down; he wouldn’t respond to my repeated entreaties to the lady on the other end of the phone. I had just completed the splitting and stacking of another Oak, my son Geoff and I had felled, a year ago, ten yards further into the forest from the Oak that is the subject of this essay. I need to continue sawing, splitting and stacking hard wood, in order to meet the winter demands of our great room woodstove.

Geoff and Jeanne told me not to fell the giant dead Oak; it was too close to the cabin they had proclaimed. Charley Bradley, my handy man and carpenter, and I agreed, however, that we could handle the job with a long rope to assist the Oak in its fall down the bank towards the stream. A bright September autumn Sunday was the perfect day for the job.

She immediately forced upon me a lifelong ban from tree felling. I understand.

I drove to Wal-Mart for a tarpaulin, while Charley began to saw the very long, imposing tree trunk down from the top of what remained of our bedroom. Later in the week, the claims man from the insurance company was very helpful. He spent an hour surveying the damage, on the roof and ground, spent another hour in his auto and emerged with a three page printed breakout of the various costs involved in returning our bedroom to a habitat,,, and a check.

Charley began the repair work immediately. His son, Jason, did the painting. Jeanne, dog Alfie and I slept in the guest room for a week. Two days ago, we moved back into our bedroom, after the aroma from the salmon-colored paint subsided. Now our focus is on preparing for an adventure in Naples, Salerno and aboard the Grande Ellade. xxx

The frustrations of travel: this is the 2nd time today I am forced to write of our adventures from the flight out of Dulles Friday evening until noon this date in Salerno: After two hours and a few hundred words written, the internet connection I purchased from the hotel failed and all was lost.

Albino has been our defacto guide since our arrival at the hotel in the dark and rain of Saturday evening, walking and dragging our roll-alongs behind us. In the morning we had landed in Vienna and lazed around the airport until our small-jet flight to Naples ascended in the afternoon. When we landed in Naples, after a total of ten hours of jet flight, we drank espresso and fought off sleep for two hours in the airport outdoor café, awaiting the 5:30 p.m. bus to Salerno.

Our “junior suite” (a bath and a half) was awarded to us Saturday evening after the air conditioning failed in our one-bath room. The suite has an ample balcony looking south over a busy thoroughfare and onto the Gulf of Salerno, a miniscule portion of the Tyrrhenian Sea. Salerno is the eastern end of the somewhat famous Amalfi Coast (the irascible novelist Gore Vidal once lived in one of the villages), which extends west to Sorrento.

Sunday morning Jeanne and I set out to take a boat ride along the Coast to the village of Amalfi. We walked briskly down the promenade fronting the gulf and over-walked our destination dock by a mile, ending at the dock utilized by boats conveying tourists to the Isle of Capri, famous for debauched night life and hoards of day-trippers. Jeanne had failed to consult the map that Albino had marked up for us until the end of the long walk. The pleasant attendants at the Capri-bound ticket office kindly tried to set us back on the correct path, as we attempted poorly to speak each others languages. The walk back to the hotel was long and slow.

Jeanne and I walked up through the narrow village alleys to the Cathedral Square, with its shops, tourists, locals with dogs and 9th Century church, approached on a huge, steep staircase; it features a 13th Century bell tower with a solid bronze door, cast in Syria, a first for all of Italy. The lemon is the signature tourist-grabber of Amalfi. Jeanne and I bought many lemon soap bars (easily packed and probably welcomed as gifts) and a bottle of “Limocello”, a semi-sweet, mildly alcoholic drink. We had done Amalfi in an hour and hustled through the crowds back to the dock and the first boat leaving for Salerno.

A wise man aboard for lunch on the Antwerp-docked R. di Genova told me: “The only people you need to be close to on a cargo ship voyage are the captain and the steward.” Then the steward was Luigi. Now it is Noly Bocboc, a short, round-faced, bright-eyed, 31 year old Filipino on his second Grimaldi contract (say it aloud, dear reader: N-o-l-y B-o-c-b-o-c, an interesting sound as it bounces off the tongue.) Luigi and I communicated predominately by hand signals, with a very few English and Italian words pitched in. With Noly Bocboc it is easy English flowing in both directions. Bocboc and an assistant serve meals in the Officer’s dining room; in addition, Noly Bocboc prepares our cabin for the cocktail hour and satisfies other reasonable requirements I might conjure. He even found a couple of martini glasses in the ship stores. Our relationship is certain to grow.

The chef is Sicilian, ergo the food is good; parenthetically, the pasta (served at least once a day) is excellent.

A day at sea is the only possible opportunity to interview the master of a cargo ship. After lunch, I knocked on the door next to ours and was invited in. Francesco de Rosa is 54 and has been a captain 30 years. It is hard to believe the math, but he insisted that he has been a ship master since he was 24 years old. Divorced, with three daughters, the youngest 12, he has a demonstrable fondness for his village, Rodi, in the Apulia region of central Italy that spurs-out into Adriatic Sea. Rodi is old; so old it was built by the founding Greeks on the Parthenon model, with the church on the top ridge, three defensive towers spanning the width of the village below the church and the homes spread out below the towers. So old, according to Captain de Rosa, that the native tongue of half of the village folk is an ancient Greek.

Captain de Rosa commands the Grande Ellade for four trips of approximately a month each, then takes 50 to 60 days off in Rodi. De Rosa appears to me, and some of other passengers, to carry his command lightly, getting the men below him to perform their duties without any huffing and puffing on his part.

Tomorrow, the captain hinted, there may be enough time ashore for the passengers to take the short journey from Piraeus to Athens, to peer up close at the original Parthenon. It has been 20 years since Jeanne and I have been in the Greek capital; that time it was a preface to a Greek Island cruise. This time, an unknown adventure will surely unfold.

Think Athens, think smog---and traffic.

Captain de Rosa told us of a supermarket 500 yards down the high speed divided highway fronting the docks. We had neglected to bring enough nuts with us to satisfy cocktail hour demand. To remedy the nut paucity, we began the walk to the market in our first adventure of the day. We initially wandered about the dock area so aimless and witless that a worker on a motor scooter chased us down and directed us out of the area. “I love America,” he proclaimed. I thought to myself that he might be a Greek in the minority.

After a long trek on the scant sidewalk beside the urban raceway, I asked a salesman in a motorcycle shop for supermarket directions; our target was in a large building located at a modest angle across the street. Once within, we couldn’t locate nuts. A middle aged woman employee walked us to them, after my plea in English. Most of the Greeks we encountered this day have a limited knowledge of English, for as the old phrase “It’s Greek to me” hints, not many in the non-Hellenic world fathom the Greek language. We returned to the ship to deposit nuts and Pepsi, expertly avoiding the trucks streaming in and out of the port area, navigating through the fence voids and security obstacles.

Jeanne and I had visited Athens almost 20 years ago, prior to a Greek island cruise and an overnight bus trip to Sophia, Bulgaria, which she has immortalized as the “bus trip from hell”, simply because luggage was piled into the rest room, rendering it useless for its intended purpose; Greek music blared loudly from speakers all night; reading lights didn’t function and our relatively expensive camera was stolen. On a rainy Athenian afternoon we had visited the 400 B.C. Parthenon, perched as it is high above Athens on the Acropolis. Now we were less that six miles from Athens with seven hours in front of us before the Captain had ordered our return to the ship; a return visit to Athens, the Acropolis and the Parthenon stuck out as the choice for the adventure of the day.

We returned to the dockside divided highway. Motorcycles, autos old and new sped by us. We waved at each passing taxi; most were engaged and gave us nary a return glance. One stopped but did not wish to go as far as Athens. More taxi waving. Finally, a yellow taxi with a young woman passenger in the front seat stopped. She was on her way to her management classes at the Athens Institute of Technology, and the driver would continue with us on into Athens and the Acropolis from there.

I don’t remember where we were on our journey through the narrow streets of the Athens area when we noticed the thick smog. It was a Los Angeles smog day on steroids. The traffic was seemingly as thick. The most noticeable detail of the slow start and go vehicular movement was how the motorcycles and motorbikes would scurry through space cracks beside and in front of cars and trucks to keep up a relatively constant pace. It must be extremely stressful for the Athenian four (and more) wheel drivers to be ever struggling to avoid injuring and killing motorized riders (often with a passenger) on two wheels.

The chief engineer goes out of his way to be helpful and lighthearted with the ten passengers aboard. When on the bridge and focused on the engine monitor at the starboard side of the ship control console he stares, speechless; at other times, on the crew/passenger living deck below, he goes out of his way to keep the atmosphere light and easy. He invariably enters the officers/passengers dining room smiling and with a quip in English.

A day filled with waiting is a good time to describe the Grande Ellade meal customs: The mid day is the principal meal of the day, beginning at 12 o’clock sharp. Pasta is the universal first course; today, it was spiral with traces of cauliflower chunks, slathered in olive oil; it is served in bowls, heaping if you tend toward gluttony. The fish course this midday was, in fact, two fish courses: delicately tomato-ed and boiled mussels in their shells, followed by large anchovies (the German couple at our table for four opined the fish species) fried and in need of a deft, knife-wielding de-boning. So much of the mussel-fish combo course was consumed, officers and passengers declined the awaiting meat and salad course. Last, large Valencia oranges were placed in baskets on the three tables by Noly Bac Bac and assistant.

Freshly baked breads are in endless supply at all meals. Butter is available only in the morning; olive oil is always on hand to moisten breads. Dinner is again three courses, with ship chef-made soups replacing pasta. Breakfast: yogurt, cold meats, breads, pizza, foccaccio, jams and coffee (Nescafe or Italian espresso.) Wine is served to passengers twice a day in small two-glass bottles. The officers are not offered wine,,,period; I don’t know if this abstemious employee policy is manifested by Captain de Rosa, or is new to the Grimaldi Empire. It is wildly in contrast to Luigi placing a liter of red and of white wine on each table twice a day aboard the Repubblica de Genova, during my long voyage to West Africa last year.

The rumor aboard the Grande Ellade is that the Repubblica di Genova, ignobly capsized at dock at the Antwerp Euro Terminal, has been vested in its insurers and, therefore, gone forever from the Grimaldi fleet. If that is true, Jeanne and I were the old girl’s last passengers forever. Strangely, I asked Captain de Rosa about the fate of the de Genova and he very formally declined to answer. The mystery of the fate of the Repubblica de Genova continues.

Another noteworthy contrast between my two Grimaldi voyages is in the quality of the autos aboard each ship. I referred to the African-bound vehicles aboard the di Genova as “junk cars”, beat up and tired after useful European mechanical lives. There is to this day a photo on our website of a mini, red wreck of a Honda, with the end of an old mattress sticking out the driver’s side window. The Grande Ellade, in contrast, carries British-made, sleek, new Hondas and Opels, all tightly lashed to the decks of the ship, as they float along to dealers in cities on our multi-nation route.

Hondas off! Fords on!

When, after dark on the Friday ending Ramadan and the Izmir ship pilots returned to their labors, the ship was able to dock we, who were looking from deck ten of the Grande Ellade, saw the area below flooded with new vehicles. In the morning they were gone. After a light breakfast, I ambled to the garage area immediately behind the living and dining quarters of the ship and discovered that the Hondas previously parked and tethered there had been replaced by Fords. Window stickers proclaim that the Fords are under the auspices of the Ford Trading Company, 1555 Fairlane Drive, Allen Park MT (sica misprint of MI) 48101. I don’t know why Ford Trading isn’t headquartered in Dearborn like the rest of the Ford Empire, but I do know that Allen Park is approximately 35 miles south of Rochester MI, where my mother, God willing, will celebrate her 98th birthday in five days.

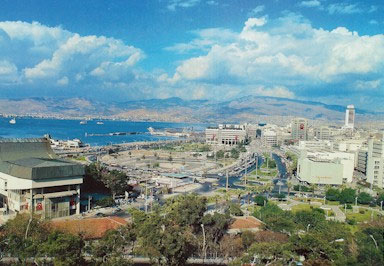

Ali Olcay Konuklu is our man in Turkey. Ali is an important functionary with the Turkish company Arkas. Arkas, in addition to operating its own ships in the Mediterranean (going to such irresistible spots as Algeria and Libya) is the port agent in Izmir for Grimaldi and its subsidiary, U.S. based ACL (standing for Atlantic Container Line). After lunch, Ali took Captain de Rosa, Chief Engineer Aloisio, Jeanne and me touring.

At nine a.m. Jeanne and I had walked off the ship with our official police-stamped crew member shore leave card. We were told to return within two hours, because shortly thereafter the Grande Ellade would be taking its leave of Turkish waters. Forget that optimism.

We encountered a virtually deserted city. Friday after sunset was the first volley in a post-Ramadan three day holiday package; I expect the celebrations had gone well into the early morning hours: Litter was abundant and few stirred but street cleaners. One exception was a baklava shop where, in the course of a purchase of four small pieces, I discovered either that baklava is almost prohibitively expensive or a dishonest merchant (honest or not, he was a handsome old man and I photographed him with Jeanne behind the counter.)

After the waterfront cruise, we ambled by a closed bazaar (holiday, you know) but stopped for a spell at a Turkish coffee shop; therein, each individual serving of stout caffeine is boiled in the cup it is to be drunk from. The coffee joint was at the cross roads of some alleys and was overhung by nets, giving it, to my way of thinking, a quasi-romantic, spies-meet-here aura. The chairs were covered in what looked to me like faux Turkish carpets. The coffee was very strong, unfiltered, with the grounds thick on the cup bottom after the last sip.

The excursion was completed with a stop at a wonderful nut and sweets shop. (The locals must have recovered from their heavy celebrating, because the streets were jammed with persons, while a young man or two sold giant blown-up balloons for the children.) Ali bought Jeanne and me over a kilo of roasted pistachios, which he assured us are more flavorful than those shaken from the trees of Iran or California. He is correct. Then, back to the ship we went.

It is a languid Sunday at sea.

While Ali drove us about Izmir yesterday, Jeanne took notice of a clash of civilizations. There we were, in a 5,000 year old city embedded in a country very strange to us; a nation that borders the exotic neighborhood of Iraq, Iran, Syria, Armenia and Georgia, and the voice of the late U.S. country singer Patsy Cline singing “Crazy” flowed from the car radio.

Friday evening the Frinks entertained at the cocktail hour. For reasons unknown, the evening meal has two sittings: six and eight. Three couples take advantage of the late sitting, one English, one Swedish and the Americans. One evening at dinner I had described my pride in the creation of dry gin martinis. The Swedish woman exclaimed that she would like to imbibe one of my martinis. Friday afternoon I invited the two couples to our owner’s cabin (suite) for cocktails.

The inevitable delays (already totaling more than a day) that the Grande Ellade has encountered has put us in a bind. Our return flights from Salerno and Vienna are for October 19; we probably will not be about to take flight until the 21st, at the earliest. Captain de Rosa mentioned that the Grimaldi head of passenger services, Mr. di Falco, has taken notice of our inability to use our current reservations. Perhaps someone in the Grimaldi office will help us make new reservations when the date of the Grande Ellade’s return to Salerno becomes more predictable.

I inquired of Captain di Rosa why wine was not placed on the officer’s dining table, as had been the case aboard the Repubblica di Genova. Lo and behold, and certainly with a sense of consternation from thousands of maritime officers worldwide, a new international regulation prohibits alcohol consumption by merchant sailors at sea. Whoa! Bad break that, but thankfully the black regulatory cloud does not rain upon the passengers.

The pressure began as soon as we exited the small ship elevator and walked down to the security desk situated at the stern ramp. A small bazaar of Egyptian trinkets, post cards, cheap sandals and other useless bric-a-brac had been established within the ship, before the ramp. Mr. Mustafa was the man we were told to deal with; he was there, with henchmen, hangers-on and a man representing himself as the ship agent.

“We take you on four, five hour tour. Nice car. Take you to new library, King Farouk palace, everything in Alexandria.” “How much?” “In Euros or dollars?” “Dollars.” “52, 53 dollars per person.”

Now granted, the U. S. dollar has tanked, dropped like a heavy stone from a high place, but it is not worthless in a soft-currency country like Egypt. The blood began to rise above my neck. The men closed around me in a semi-circle. I sidled a few steps away. “No, we don’t need all that. We don’t want a four hour tour. We’ll just go out of the port and get one of those little black and yellow taxis,” I said. Kenny, an 80 year old Swedish fellow passenger, and his wife (two of the four guests at our cocktail party) were of a like mind. The four of us walked down the ramp from the ship. The coterie of Egyptians followed.

“Which way is the gate?” I asked them, as I began a parade of Americans, Swedes and Egyptians into a lane of stacked containers. “Too far for you to walk.” We walked on.

At this time, a tall, dark-skinned, Egyptian hustler approached and said: “I’ll take you in my car to the center of the city for $10 for all of you.” He offered a reasonable priced escape from the great Mr. Mustafa, the alleged ship agent and crew. Away we went. Before we got to the port gate we had negotiated with our new Egyptian, Mohamed Ali, to take us on our custom-designed tour for $20 a head.

Today was the last of a three day Muslim holiday commemorating the end of Ramadan. Our driver kept referring to the day as “Christmas,” a misnomer of colossal misinterpretation. Clearly, a holiday spirit was rampant throughout the broad avenues and city streets we drove: festive fairs, with skinny donkeys providing street-side rides for children, balloon venders and casual loitering by Alexandrians of all ages.

As we sped along the seaside, separated, multi-laned , Corniche highway on our nearly 40 mile roundtrip mission to the palace by the sea of the late and last king of Egypt, Farouk I, I was impressed with how well dressed and satisfied the persons on the paseos appeared. Some women wore religious garb from head-to-toe, eye-slit-open-only black or grey garments, Most wore colorful head scarves, sometimes with matching long gowns, or more often with the young, tight, denim jeans. Some women we sighted from our old, blue, tourist station wagon dressed without regard to Muslim custom. “How many Coptic Christians are there now in Egypt” I asked Ali. “About 25%”, he replied (according to him out of a national population of 77 million, seven of those Alexandrians.)

On our journey, we passed dozens of cafes facing the sea, patrons sipping tea or smoking from Arabic, long-hosed contraptions. We saw long bathing beaches, spotted with large, blue-striped, shade umbrellas. We passed many hotels that from first blush I wouldn’t care to stay in, and two, The Four Seasons and Sheraton, where I probably couldn’t afford the tariff.

When we arrived at fat Farouk’s palace (he was an obese poster child of decadence, often photographed lounging in a nightclub, wearing round, dark sunglasses, usually in the company of comely, young women) it was closed. It is always closed, unless one is a friend of the Egyptian president, Hosni Mubarak, which to our misfortune, we were not.

Eager for a beverage before returning to the Grande Ellade, Ali drove us to a large, sparkling new shopping center. Jeanne and I each enjoyed a Starbucks iced, mocha coffee, price in dollars, eight.

A knock on the door awakened us at 1:35 a.m. I staggered naked out of the bedroom to the cabin door; no one there. Knocks on the Captain’s door often sound as if they are meant for us. Again, three hard raps, this time clearly on our cabin door. When I opened it the second time a crewman said: “Immigration wants to see you.” Jeanne and I dressed hurriedly.

We entered the ship conference room and were told to sit at the end, facing the Captain; we were flanked by three Israeli women, two dressed in black (both stern, one obese) on our left, sitting next to the Captain; to my right, a young blond woman in a grey uniform. “You must wonder why I called this meeting,” I opened the repartee. No one smiled. The Captain winced.

“Have you been to Israel before?” the woman in grey began the questioning. “Why have you come to Israel? Where are you going in Israel? Are you going to stay in Israel?” “Not if the Captain will let us back on the ship,” I replied. “He will,” she said with only a slight smile. So our day began.

While in line for our security interrogation I observed a young man with skin tint significantly darker than the norm in the Mideast. “An Ethiopian,” I said to Jeanne, remembering the Israel airlift of Ethiopian Jews out of the African nation decades ago. He was the ship agent for Grimaldi in Ashdod. “Anyone want to go to Jerusalem? The ship will be here 25 hours.” he blurted out to the barely-awake passengers “Two, for sure,” I assured him. He set the ground rules: a vehicle would meet us after breakfast, the driver/guide would stay with us throughout the round trip, ship to Jerusalem to ship. Nothing was said of Bethlehem. If only the two of us accepted the offer, the price would be $100 per person. Well, not exactly.

Nine a.m. at the stern ramp security desk we received our passports from one of the 3rd mates. The driver arrived in a diesel-powered van large enough for a group of ten. I sensed something awry on first blush: The driver’s English was rudimentary at best; no tour guide he. We reestablished the price and boarded. The port immigration office was the first stop. With behind-the-counter scowls, we were handed our shore leave cards, complete with photos copied from our passports. Strangely, with all our travel documents now in order, the port gate multi-person inspection of them took so long our driver pulled off to a side lane in anticipation.

At last, we were on our way to Jerusalem; again, not exactly. A few miles out of the Ashdod urban traffic scrum the driver, who was also balancing the operation of two mobile phones, handed one to me and announced: “It’s Isaac.” “Hello, I’m your guide,” the cell phone voice pronounced. I explained to our new “guide” the arrangement I had made with the ship agent and that I was not in the market for an add-on. “You can pay me what is in your heart.” “I have a heart of stone,” I replied. It was Isaac who informed us that we were on our way to Bethlehem, not Jerusalem.

Somewhere along the far outskirts of Bethlehem the driver pulled into an out of the way spot at a gas station. “Isaac will be here in four minutes. This Israeli vehicle can’t enter Palestine,” informed our driver. I was furious, but trapped. I wanted to begin our adventure in Jerusalem, take as much time as needed and if there were time, travel the four or five miles to Bethlehem, where Jeanne could visit the Church of the Nativity.

Isaac arrived in such a wreck of a compact car it might have been rejected as a Grimaldi-conveyed junk car to West Africa. Our first stop was at Isaac’s curio shopsurprise, surprise. I had mentioned my wounded camera. Isaac sent it out to a nearby camera shop to ascertain its reparability, if any. There was none. We bought a throw-away 35 millimeter camera, in the hope of catching some of the images of the day.

On to Jerusalem. When the time finally arrived for our excursion to Jerusalem, I was mildly surprised when Isaac’s assistant joined us in the dilapidated car. Isaac drove. We were a short distance from the new steel wall the Israelis constructed, separating portions of Palestine from the Jewish state. “Look how it separates us. People tend fields they can no longer see from their homes,” said Isaac, a self-professed Roman Catholic Arab. The wall is impressive: very high, made of slate grey steel; too tall to vault over; too slick to scale. Any anti-tunneling provisions would be, of course, invisible to the eye.

We arrived at an entrance-exit point in the wall. It looked to me like the entrance to a high security prison. Three of us exited the car; the young man drove it away. Within high steel walls, we entered a warren of electronically controlled revolving steel gates and metal detecting devices. The Palestinians removed their belts and other alarm-triggering metal; by showing our passports to young soldiers behind thick, assumed-to-be bullet proof, glass Jeanne and I were exempt. Above, on a cat walk a young Israeli soldier patrolled, cradling an automatic rifle. Finally, we emerged into Israel, where our driver and van were waiting. “That was scary.” Jeanne exhaled.

I wanted immediately to enter old Jerusalem through the Jaffa Gate. Isaac wanted to give Jeanne a panoramic view of Old and, widespread, New Jerusalem. Isaac got Jeanne’s nod and we proceeded to a scenic overlook created with money from the American fortune of the Haas family, of Levi-Straus jeans fame. The overlook vista placed the tiny, old city in proper, greater-Jerusalem prospective.

While Isaac pointed out to Jeanne the Tower of David, where the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate tried Jesus and ordered his crucifixion, I slipped into an Arab café near the gate to inquire about Mr. Nasser, a silver-haired Coptic Christian (father of a son, Sami, who at that time owned two tobacco shops in Bakersfield CA), who had befriended and educated me in the ways of Old Jerusalem; alas, no news.

Our procession of three stopped at the Christ Church guest house, in a brief dip for me into Old Jerusalem nostalgia. A few doors further up Armenian Patriarchate Road, I hit my nostalgia pay lode: During my week in Jerusalem I had ordered and received custom painted ceramic wall plaques, unique Jerusalem gifts for our sons and their families, from the Armenian Art Studio. When I again walked down into the shop, the owner and ceramic artist, Vic Lepejian, sat paint brush in hand exactly where I left him, lo those many years ago. His son (whom I immediately tabbed “Vic Junior”) sat at his side, also painting a slab of ceramic. We chatted and Jeanne bought some Vic-created gifts.

Now it was quick-walking up and around the Armenian section of the Christian Quarter, into the Jewish Quarter, past the restored Roman market and into a narrow alley overlooking the Western (Wailing) Wall and the praying Jews. This Jewish holy place, all that remains of the Temple of Jerusalem, sits directly below the Al-Aqsa Mosque and the golden Dome of the Rock, the 3rd most holy place in Islam. Perhaps no other scene on earth signifies how intertwined the three great western religions are springing, as they did, from the dot of barren soil that is Jerusalem. It also, unfortunately, illustrates why the Muslim, Jews and Christians are locked in a struggle for control of Jerusalem, a struggle doomed to last into millennia unforeseen. Jeanne and I posed for photos, our backs to this ironic historical tableau.

Jeanne’s most emotional moment in Old Jerusalem was upcoming. She wasn’t prepared for the moments we spent in the church built around the place where scholars believe Jesus was interred: the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The broad, sunlit court yard contrasted to the dim light of candles lit by the devoted and the rather dim electric illumination.

Following a nun in habit, Jeanne knelt down and touched the spot where Jesus’ body is said to have been first laid on the earth. Then, we joined tens upon tens of persons peering into the crypt; many wait long periods to make a short visitation into the tiny inner sanctum, but time demands and claustrophobic concerns overruled any desire for such an experience. Later on in the van, tears welled in Jeanne’s eyes as she described the profundity of her experience in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

Up the long line of stone steps passing the Arab merchant stalls (spices to supposed antiquities) we strode. We reached the top, swept past the cafes and the Israel tourist office and out the Jaffa Gate. The van and driver were waiting. We were on our way back down to the seacoast and the docks of Ashdod. Before Isaac was disgorged from the van, Jeanne did some retail business with him in regard to the alleged Armenian handmade silver crosses. Isaac and the Frinks all had a fruitful day in Jerusalem.

The passengers have jumped ship – or at least most of them.

Cyprus is the part time home of two of the couples already on board when we joined the ship in Salerno. The Swedish cocktail-drinking couple, who accompanied us on our Alexandria station wagon dash to King Farouk’s palace and back, met when she sold him his, now their, Cyprus apartment. She was married to a Cypriot, has a son in the country and lived there for 20 years. The German couple has acquired a ramshackle homestead in a mountain village and they have plotted out the next five winters to reconstruct it into a suitable home.

“I would like a report from you in five years,” Birgit (the Swedish female and veteran Cyprus resident) said at dinner one evening. “Why, what do you mean?” retorted Nick, of the Nick and Nicki English team. “Things are often not as they seem in Cyprus,” Birgit replied. Her veiled warning fell on unwelcoming ears. “We’ll be fine. Oh, there might be a few inconveniences here and there, but we’ll get through it,” replied the retired British Army Major, with the stiffest of upper lips. “I would still like a report,” Birgit came back.

The three couples and their accompanying cars were offloaded shortly after our 5 p.m. docking yesterday in Limasol.

The remaining Swedish couple is on a 37 day Sweden to Sweden round trip on the Grande Ellade. They are very pleased with their voyage and are considering a 60 day South American Grimaldi voyage next year. They saw what remains of the Repubblica di Genova when the Ellade docked in Antwerp. They told us at lunch today that the di Genova has been righted, that she is very low in the water (the hull is probably flooded) and that her starboard side (which was in the water) is a complete mess. “It frightened me to see her like that when we, you know, are taking this ship for long voyage,” Elizabeth (of the Swedish team of Elizabeth and Kennert) said, and changed the subject.

I was just summoned next door to the Captain’s office to take a call from Carlo di Falco, a Grimaldi manager in Naples. He, and the recently retired Grimaldi passenger service manager Hans Isler, have helped Jeanne and me out of a sticky jam (of course, all jams are sticky.) Because of the two day delay in the Grande Ellade return to Salerno, our flight reservations out of Naples are dead as yesterday’s losing lottery ticket. After much effort, Mssrs. Di Falco and Isler have confirmed that we will have seats aboard requisite jetliners Tuesday to Munich and Washington Dulles.

Again, to make superficial comparisons between my voyage on the Repubblica di Genova and the Grande Ellade: The Grande Ellade cruises the Med at 18 knots, the di Genova cut through the South Atlantic at 16 knots; the di Genova was 720 feet long (if memory serves), the Ellade 510 feet in length. The di Genova was the first Grimaldi roll-on roll-off ship; the Ellade (2001) one of the latest. The di Genova carried a crew of 28, the Ellade 30 (I believe the second officers/passengers steward and a kitchen cleanup guy working this ship account for the disparity.)

The Chief Engineer approached me coming down the passageway leading from the corner formed by the captain’s suite and ours (the owner’s). He was wearing his engine room Grimaldi blue coveralls. He paused in front of me and held up an index finger; I sensed the command was for me to do the same – and did as my instincts instructed. The Chief withdrew a circle of string from his pocket; with an elaborate motion, he tied it around my erect index finger. Then, he bent down and blew on the knot. The knot and string fell from my finger. He laughed merrily at his Chaplin-like silent sight gag and was on his way. The Chief and his string gag are an apt metaphor for this voyage: loose and light.

This morning I entered the bridge to learn when we would be passing through the Messina Strait. The Captain was there. I mentioned again that I had observed a happy ship, at least reflected by the officers and cadets I have encountered. “It just appears to me that men do their work best if they are not stressed. Ours is a difficult life,” Captain de Rosa replied. I remember my friend Adrian, the Romanian first mate on my long di Genova voyage: It was clear to me that he was tense and under stress every moment aboard the di Genova.

Today at noon we sat down for our second and last meal with the remaining passengers, the Swedish couple, Elizabeth and Kennert. “You know, I wasn’t born in Sweden, I’m Hungarian,” Elizabeth began a tale. “In 1956, when Russians sent tanks to Hungary, I was 15 years old. My family sent me from my village 60 kilometers away to see about relatives in Budapest. We had not heard. When I got there, the house was gone, you know, bombed. People had to be off the streets at 5 p.m.” “A curfew,” I interjected. “Yes, a curfew. Family next door took me in; they had 15 year old, just like me. “They had papers to leave country, with their children. So they took me with them.” As Jeanne and I understood it, they went first to England. How Elizabeth got to Sweden is not clear. Once there, the Swedes put her in a school that taught her the intricacies of ladies millinery creation. With her first husband, she served for a year as second cook on a Swedish ship that delivered Volvos to Jacksonville, then went on to Guayaquil, Ecuador for the return cargo and loaded Chiquita Bananas. “I couldn’t be first cook, you know,” then spread her arms wide above her head, demonstrating that her physical limitations would not allow her to do the heavy work. She is tiny, her growth obviously somehow stunted. Her spirit, however, is full-sized. An interesting conversation on our last day aboard the Grande Ellade.

The ship is passing through a cold front; for the first time, the sea is white-capped and rough, the port to starboard rolling constant.

A morning docking has turned into an afternoon affair. We are presently dead in the waterwaiting. The biggest cause of cargo ship delays is the wait for port of call dock space to become available. That is the fact of cargo ship travel, and if you have to fly commercially to reach your ship and reverse the routine when disembarking, costly airline reservations changes are inevitable. On the bridge this morning when the Captain told me of the delay, I responded: “Oh, another free meal.”

Jeanne didn’t accept dinner last evening. She did not get seasick, simply was a little queasy. The rough seas continued through the night. Bed is the place to be in rough weather and high seas shipboard: The low center of gravity reduces the swing and sway (how many remember the band leader Sammy Kaye?)

The Pope is in Naples today. We will eventually be on our way there. Traffic will be a mess, as it was in Bethlehem a few days ago when Secretary of State Condaleeza Rice was in town meddling in Palestinian-Israeli problems. Jeanne and I were once in Dublin when Prez Ronald Reagan was in town. Visiting bigshots cause traffic problems, jams, whatever.

It has been a joyful experience being back aboard a Grimaldi ship – albeit for such a short journey. Jeanne and I thank Captain de Rosa and his entire crew and our friends Hans Isner and Carlo di Falco, in the Grimaldi management offices in Naples.